|

| Children at the Yezidi refugee camp in Batman, Turkey/Credit: Kimbal Bumstead |

Refugees from Iraq's Yezidi (or Yazidi)

religious minority, who have fled to Turkey from the advance of jihadists, are still

living in harsh conditions in refugee camps.

And many fear they will never be able to return home.

The Yezidi refugees have fled to the

southeastern Turkish province of Sirnak bordering Iraq to escape the murderous

advance of Islamic State (IS) jihadists who specifically target their

community.

Turkey, which is already giving sanctuary to

some 1.2 million fleeing the Syria conflict, is not coping with this

additional refugee influx.

Kimbal Bumstead, a young

British-Dutch artist, has spent some time in the Yezidi refugee camp of Batman.

Here is his report:

Five minutes walk from

“Batman Park”, a monster of a shopping mall, complete with lights that change

colour, glass elevators and chocolate fondue fountains, is a disused football

ground building that houses over 500 Yezidi refugees who have fled from Sinjar,

Northern Iraq. They have been living

there for over a month now, with three families to a room, after ISIS militia

came to their village massacring those who refused to convert to Islam.

The Yezidi people are a

Kurdish tribe who follow an ancient Mesopotamian pagan religion in which they

worship the sun, and have a spiritual connection with the land.

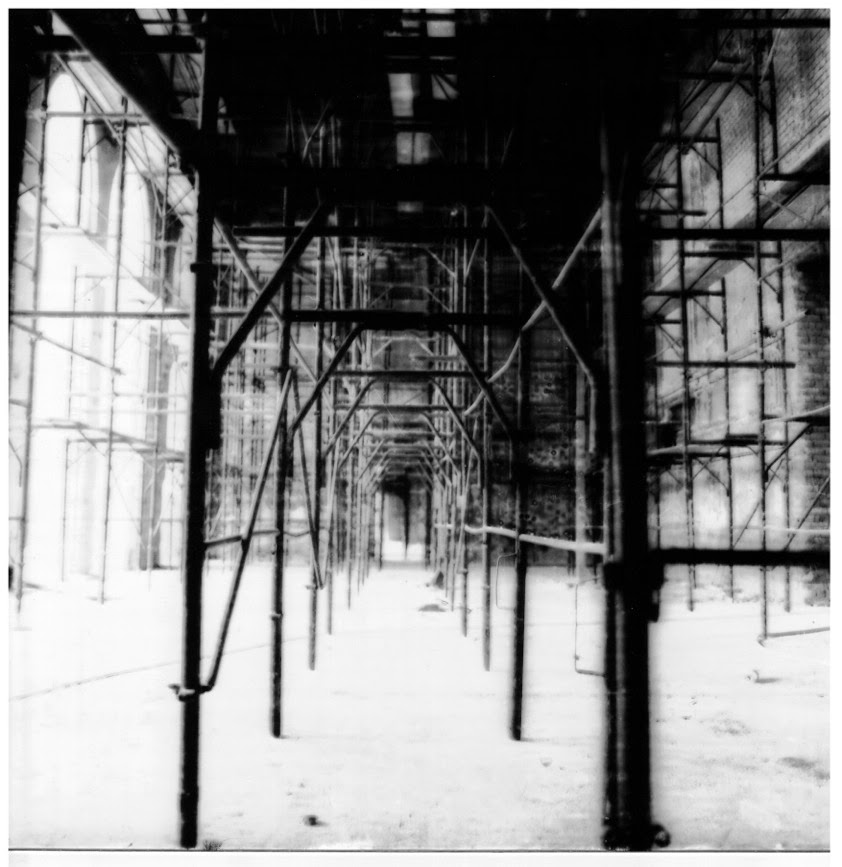

|

| Credit: Kimbal Bumpstead |

I was lucky to meet two

men there who spoke English, having been interpreters to the US Army during

military campaigns in Iraq during 2007/2008. They told me some horrific stories

about their families and friends who had been killed, women raped and sold into

sexual slavery. On the 3rd August, ISIS militia came to their

village and took 80 men out into the street, and told them they must convert to

Islam or they will be killed. Those who refused were shot; those who accepted

were also shot.

According to local news

sources there are now over 30,000 Yezidi refugees in Turkey, having fled their

villages on foot, it is estimated that there are over 1 million refugees in

Turkey now since the start of ISIS attacks in Syria and Iraq.

A place in-between, a life in limbo

The disused sports hall

housing the refugees is a place in-between, a place of not knowing, and hopes

that may be shattered. There is not enough room inside the building or enough blankets

for everyone to sleep. Many of the men are sleeping outside. The winter is

coming and the people I spoke to have received no information about where they

can go or when.

They have not been granted

asylum in Turkey and neither do they want that. All of them have the same

dream: to move to a place that is safe, in either Europe or America. They want

permanent solutions and asylum, but for now they are in limbo, not having the

tools or the means to be able to apply for it. Without having money to travel

to an embassy, nor documents, they are reliant on officials to come to them.

They are becoming increasing frustrated, and none of them know how long they

will have to wait.

The majority of them are

undocumented, having left their homes with just the clothes they were wearing,

many of them had never had the need for a passport before. Turkey has granted

them temporary shelter in its territory, but not political asylum.

“We want to go to Europe

or America”, says Saado, one of the former US interpreters, “we can’t go back

to Iraq, it’s not safe, they will kill us, but we can’t stay in Turkey either.

Maybe they will make us stay here for one or two years but then what?”

Another man, a Kurdish

Yezidi who lives in Batman and has taken it on himself to organise the camp,

tells me: “The Turkish government say

they are helping, but they are not doing anything to help us. The only help we

are getting is from the local Kurdish community, they give us food and water

and have helped with giving us blankets to sleep on, but we need help from

governments. People see us but they

are blind to us, we need help… Even the animals have rights, if they can’t give

us human rights, at least give us animal rights.”

|

| Credit: Kimbal Bumpstead |

"74th recorded genocide of Yezidian peope"

Turkey is a comfortable

buffer zone for ‘Fortress Europe’, literally a space in-between, to help delay

responses in helping to take in refugees. For how long these people will have

to wait, for politicians to make decisions about their futures, they do not

know.

The message from the

refugees is clear, that they do not want to stay in Turkey, they are afraid of

the possible future reprisals of Islamic fundamentalism and possible attacks

here. I asked a boy what he thought about the future. He said that he couldn’t event think about the

future, everything was gone. He just wants to be able to go back to school and

feel safe. I asked if he felt safe here. “No”, he said, “I am afraid that those

people will come here too”.

Saado expands, saying that

if Turkey really wanted to help then they would help by attacking ISIS, not by

supplying them with weapons and supporting their actions.

Meanwhile, out on the

streets of Batman, police in armoured tanks are firing tear gas at a group of

protestors angry about the Turkish Government’s lack of support to Kurdish

Guerillas who are fighting ISIS in the Syrian/Turkish border village of Kobane.

This is the 74th

recorded genocide of Yezidian people in history, as Saado tells me. “This happens to our people every 100 years or

so. The past 100 years alone has many cases of Yezidians being persecuted both

in Iraq and Syria ,but also within Turkey. Turkey used to be home to a large

proportion of the Yezidian population, but following the Ottoman led genocide

during the years 1915-18, in which around 300,000 Yezidians were killed, plus

further attacks after the creation of the Turkish state, most Yezidians fled to

neighbouring countries. Stories are passed down through generations and their

fears and lack of trust in the Turkish state is heavily apparent. Those I spoke

to, made it clear that this is a religious problem, not a political one. ISIS

wants to kill them because they believe they are devil worshipers, and the

Turkish state does not officially recognise Yezidism as a religion.

Interestingly, Turkey is classified by the United Nations as a ‘secular state’,

however it only recognises three minority religions; Greek Orthodox Christians,

Armenian Orthodox Christians, and Jews. Those Yezidians, and those of other

minority religions such as Syrian Christian, Chaldean and Bulgarian Orthodox

who live in Turkey are classified as either atheists or as Muslim.

“It’s chosen by god, (this

genocide),” the other interpreter tells me. I ask why he thinks god would want

that. “I don’t know”, he says, “maybe

this is not our place, maybe this is our destiny.” There is a sense of bad

‘kader’ (destiny) amongst Yezidians,

which I imagine many Kurdish people also can relate to. Having a shared history

of being persecuted by the states that encompass them. These are placeless

people, and now they do not even have a home.

Are you hopeful that

something will change I ask? “Yes we hope,” he says, and looked down at the

ground. “but until now we did not hear anything…. Maybe we are hopeless….” He

smiles, and looks out into the yard.

In the yard, under a

blanket propped by a stack of chairs, a group of children watch a TV. On the

screen are images of American jets. They are excited, people welcome the latest

bombings, but it’s not enough, “they are just putting on a show”, another man

told me. “They are just securing their oil once again, rather than actually

doing something to help the people”.

|

| Credit: Kimbal Bumstead |